This is pretty great. I scored the highest in Paul Tillich. Let me know who scores highest for you. Take the test at this link:Which theologian are you?

This is pretty great. I scored the highest in Paul Tillich. Let me know who scores highest for you. Take the test at this link:Which theologian are you?3/31/2006

Theologian Test

This is pretty great. I scored the highest in Paul Tillich. Let me know who scores highest for you. Take the test at this link:Which theologian are you?

This is pretty great. I scored the highest in Paul Tillich. Let me know who scores highest for you. Take the test at this link:Which theologian are you?3/30/2006

Strangely Warmed - A Good Source for Wesleyan News

My brother and I are proud to announce the launch of Strangely Warmed, the web blog for all things which are newsworthy within The Wesleyan Church.

Feel free to peruse the site, make comments, and, of course, tell a friend.

The address is www.strangely-warmed.blogspot.com.

For those who subscribe to a newsreader service, the site is fully RSS compatible.

/end gratuitous self-aggrandizement

3/22/2006

Now That's a Close Shave...

My generation is special. Sure, we had Nirvana; MTV 2; those obnoxious snappy wrist bands and, really, the internet (move aside Al Gore). However, our most amazing claim to fame is that we have been blessed to grow up watching the evolution of the razor. The Trac II came out right when about most of us were old enough to watch our dads slicing their faces to shreds with standard one-blade razors. The Trac II really revolutionized the shaving industry (I mean, c'mon, two blades!), and spurred development in other areas (facial care creams, smoother aftershaves, real "silk" leg lotion, etc.).

My generation is special. Sure, we had Nirvana; MTV 2; those obnoxious snappy wrist bands and, really, the internet (move aside Al Gore). However, our most amazing claim to fame is that we have been blessed to grow up watching the evolution of the razor. The Trac II came out right when about most of us were old enough to watch our dads slicing their faces to shreds with standard one-blade razors. The Trac II really revolutionized the shaving industry (I mean, c'mon, two blades!), and spurred development in other areas (facial care creams, smoother aftershaves, real "silk" leg lotion, etc.).And yet technology would not be slowed. In the subsequent years, another blade was added, and then another. Now we are the proud generation that regularly uses 5, yes!, 5 blade razors! How do they get them all on there? That's science for you.

Recently, some math wizards completed a statistical analysis of the evolution of the razor throughout history. Given the exponential growth within the last 5 years, the number of blades will quickly increase. As shown above, using a normal hyperbolic curve, it appears that the number or blades per razor will reach infinity by 2015--only 9 years from now.

The brightest minds of science are currently racing to create technologies to keep up with the evolution of the razor. But what, exactly, will the eventual Infini-razor mean for the consumer?

Well, the inclusion of an infinity of blades on one razor will mean that the potential cutting power of an infinite number of blades will remain suspended in superposition throughout the course of the shave. In laymans terms, this simply means that in an infinite number of universes, you will have the closest shave of your life before you even think about shaving.

That's quantum physics...

That's applied science...

That's the closest darn shave you'll ever have!

3/17/2006

The Man Behind the Day

displys of everything green. However, the day is meant to be so much more.

displys of everything green. However, the day is meant to be so much more.On this day, we commemorate St. Patrick. A fifth centruy (387-484 C.E.) British Christian, Patrick was kidnapped at the age of 16 by the pagan Irish. After spending 6 years in captivity, Patrick received a dream in which a voice told him to return to the British mainland. Seeing this as a divine command, Patrick escaped, returning to his home. After studying for many years in the continental monestaries, Patrick was sent by Pope Celestine to return to Ireland to evangelize its peoples. For the next 33 years, Patrick worked amongst the Irish, eventually converting the entire people to Christianity.

Because of Patrick's work amoung the Irish, the Christian faith flourished in Ireland. Many monestaries were established which soon became active and influential centers of learning. In fact, during the breaking apart of Christendom under the invasions of Islam during the Middle Ages, the monestaries in Ireland were virtually the only centers where Christian literature from centuries past was preserved. Without the Irish monestaries, many of the patristic writings that are widely available today might no longer be extant. In this way, modern Christianity owes much of identity and history to St. Patrick's work.

Hopefully, our remembrance of his work and sacrifice for the cause of Christ will be more substantial than waking up with a hangover tomorrow...

Let me leave you with some selections from St. Patrick's writings:

I came to the Irish people to preach the Gospel and endure the taunts of unbelievers,

putting up with reproaches about my earthly pilgrimage, suffering many persecutions, even bondage, and losing my birthright of freedom for the benefit of others. If I am worthy, I am ready also to give up my life, without hesitation and most willingly, for Christ's name. I want to spend myself for that country, even in death, if the Lord should grant me this favor. It is among that people that I want to wait for the promise made by him, who assuredly never tells a lie. He makes this promise in the Gospel: "They shall come from the east and west and sit down with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob." This is our faith: believers are to come from the whole world.

putting up with reproaches about my earthly pilgrimage, suffering many persecutions, even bondage, and losing my birthright of freedom for the benefit of others. If I am worthy, I am ready also to give up my life, without hesitation and most willingly, for Christ's name. I want to spend myself for that country, even in death, if the Lord should grant me this favor. It is among that people that I want to wait for the promise made by him, who assuredly never tells a lie. He makes this promise in the Gospel: "They shall come from the east and west and sit down with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob." This is our faith: believers are to come from the whole world.(From the Confession of Saint Patrick)

“I bind to myself today The strong power of the invocation of the Trinity; The faith of the Trinity in unity; The Creator of the elements. “I bind to myself today, The power of the incarnation of Christ With that of His baptism; The power of His crucifixion With that of His burial; The power of the resurrection With (THAT OF) the ascension; The power of His coming To the sentence of judgment... “I bind to myself today, The power of God to guide me, The might of God to uphold me, The wisdom of God to teach me, The eye of God to watch over me, The ear of God to hear me, The Word of God to give me speech, The hand of God to protect me, The way of God to prevent me, The shield of God to shelter me, The host of God to defend me, — Against the snares of demons Against the temptations of vices, Against the lusts of nature, Against everyone who would injure me Whether far or near, Whet her few or with many. “I have set around me all these powers, - Against every hostile, savage power Directed against my body and my soul; Against the incantations of false prophets, Against the black laws of heathenism, Against the false laws of heresy, Against the deceits of idolatry, Against the spells of women, and smiths, and Druids. Against all knowledge that blinds the soul of man. “Christ protect me today, Against poison, against burning, Against drowning, against wound, That I may receive abundant reward. Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ within me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ at my right hand, Christ at my left, Christ in the fort (when I am at home), Christ in the chariot-seat (when I travel), Christ in the ship (when I sail). Of the Lord is salvation; Christ is salvation; With us ever be Thy salvation, 0 Lord! “Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me, Christ in the mouth of every man who speaks to me; Christ in every eye that sees ‘me, Christ in every ear that hears me.”

(H. A. Ironside, The Real St. Patrick, Loizeaux Brothers, New York, Pp. 13 - 14)

3/16/2006

'DNA Origami' Creates Map of the Americas

NewScientist.com news service

Duncan Graham-Rowe

A map of the Americas measuring just a few hundred nanometres across has been created out of meticulously folded strands of DNA, using a new technique for manipulating molecules dubbed "DNA origami".

created out of meticulously folded strands of DNA, using a new technique for manipulating molecules dubbed "DNA origami".

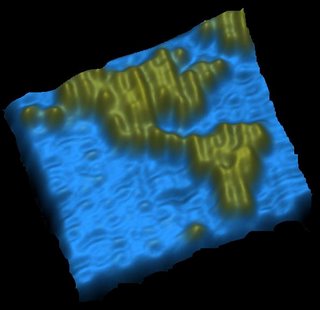

The nanoscale map, which sketches out both North and South America at a staggering 200-trillionths of their actual size, aims to demonstrate the precision and complexity with which DNA can be manipulated using the approach.

According to the map's creator, Paul Rothemund at Caltech in Pasadena, US, DNA origami could prove hugely important for building future nano-devices including molecular machines and quantum computer components. The technique exploits the fact that complementary base pairs of DNA will automatically stick together and involves folding a single strand of DNA in many different ways.

To make the nano-map, Rothemund first needed to create a suitable "canvas". He used a single strand of DNA from a bacteria-destroying virus called M13 mp18. The strand was folded over and over at regular intervals using smaller strands of complementary DNA, which pull t wo parts of the strand together to create each fold.

wo parts of the strand together to create each fold.

The result is a flat surface made from a long double helix, comprised of the single long strand and more than 200 shorter strands stuck along its length, "stapling" it together at key locations.

Quantum dots

If this helix was a perfectly formed, the canvas would appear blank. But by using short strands of DNA, containing bits that do not stick to the main strand, it is possible to cause parts of the canvas stand out . Precisely controlling the location of these extra bits made it possible for Rothemund to draw out the shape of the map.

To make the design process less complicated, Rothemund created software that works out which short-strand sequences will generate different shapes. Rothemund says it should be possible to precisely arrange quantum dots or carbon nanotubes after chemically binding them to DNA, using the method.

William Shih at the Biomolecular Nanotechnology Group at Harvard Medical School in Boston, US, says this offers the most flexible method yet for building nanoscale structures. Shih is experimenting with the technique as a means of making molecular 3D cages, which could be used to build molecular motors.

Disposable scaffolds

It is not the first time DNA has been used to make structures - the idea was originally developed by Nadrian Seeman at New York University, US - Rothemund's approach takes things to a new level of complexity.

Although Rothemund has only made 2D shapes there is nothing to prevent the technique

being applied to make complex 3D structures, he says. These could serve as disposable scaffolds to help molecules and carbon nanotubes self assemble.

Other examples "DNA artwork", creating using the same technique, include "smiley-faces", complex geometric shapes and a picture of a double helix with the letters "DNA" running above it.

Death, Darwin and Penal Substitution

A. The “penalty” of sin is death.

B. Humanity has sinned.

C. Therefore, humanity deserves to and must die.

D. Christ has paid the “penalty” (deserved debt) of sin by dying in humanity’s place.

Admittedly, this is logical, straightforward, and it preaches really well. However, despite the prima facie appeal, PSA theory is based upon several false premises and is subject to many philosophically incoherent conclusions. In the following, I shall attempt to explicate exactly what these are. Moreover, I shall attempt to briefly note how these issues relate to recent reevaluations of the structure of the universe and the nature of death.

To begin, let us examine the first statement: “The penalty of sin is death.” Based upon the oft quoted words of Paul (“the wages of sin is death”), PSA theory necessitates that physical death is the causal product of sin (however this may be conceived). If one is to speculate back to the Genesis story of the Garden of Eden, such a view naturally and necessarily concludes that Adam, before the genesis of sin, lived in a state of non-death. In other words, were one to envision a reality in which Adam’s sin is a non-reality, one must conclude that Adam, in such a state of innocence, would have lived perpetually, never to experience the cessation of biological life. Until recent years, the above might be considered the “orthodox” view of Christians concerning the relationship between sin and biological death, and even still this perspective enjoys wide-spread assent in many sections of the Church.

Nonetheless, the question must be raised, “Is this a helpful view?” And even more importantly, “Is it right?”

Darwin and Rethinking Death

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Charles Darwin outlined what has com

e to be known as the “theory of evolution” in his seminal work, Origin of the Species. Within only a few years of its publication, Darwin’s work was received with great excitement by the scientific community and his theories and methodological principles were incorporated into various disciplines—from biology and astronomy to sociology and behavioral development. Initially, many within the Christian community embraced Darwin’s ideas, for they saw in his work a creative opportunity to further link theology and religion to the revolutionary advances in human knowledge that were just beginning to occur. To these sympathetic believers, Darwin’s theories confirmed their belief about the wonder, splendor and uniqueness of God’s creative acts in history. Nonetheless, it was not long until fierce opposition arose from within the then-emerging fundamentalist movement, attacking Darwin’s theories as “atheistic” and anti-Christian.

e to be known as the “theory of evolution” in his seminal work, Origin of the Species. Within only a few years of its publication, Darwin’s work was received with great excitement by the scientific community and his theories and methodological principles were incorporated into various disciplines—from biology and astronomy to sociology and behavioral development. Initially, many within the Christian community embraced Darwin’s ideas, for they saw in his work a creative opportunity to further link theology and religion to the revolutionary advances in human knowledge that were just beginning to occur. To these sympathetic believers, Darwin’s theories confirmed their belief about the wonder, splendor and uniqueness of God’s creative acts in history. Nonetheless, it was not long until fierce opposition arose from within the then-emerging fundamentalist movement, attacking Darwin’s theories as “atheistic” and anti-Christian.There were many reasons for this opposition. One of the more obvious and popularized reasons was the exaggerated way in which some in the Christian community described Darwin’s theory of human evolution, i.e., “monkey’s uncle.” To some, the idea that humans derived their existence from a “lower,” less evolved form of life was reprehensible. Not only did the time frame of the evolutionary theory contradict literalistic interpretations of the creation narratives in Genesis, but moreover many felt that it downgraded humanity’s createdness in the imago dei, the image of God. After all, they argued, if humanity is merely the product of an improvement on a lower species, how is humanity special?

Another main reason for the groundswell of opposition to Darwin’s theory was that many believed (and still believe) the concept of evolution overturned the doctrine of original sin. As mentioned before, the classic formulation of sin at the time was that “the penalty of sin is death.” Therefore, many could not understand how to effectively hold both evolutionary theory (which requires millions of years of biological death) and classic Christian conceptions of sin in harmony with one another. “How can the penalty of sin be death,” these wondered, “if death is a natural part of the creation?”

As is obvious, the atonement theology of these individuals—as well as many within the contemporary context—effectively determines their assessment of scientific theory. Therefore, the question must be asked, “Is this a correct assessment?”

It must be admitted that it is becoming more and more difficult to maintain “classical” conceptions of death as resulting from the “fall” of humanity. Before Darwin’s contributions, it was more or less the Christian community’s “word” against that of anyone else concerning the origins of creation, humanity and—in our interests—death. However, with Darwin’s theories, an entirely new organizational principle was offered which provided a structure for interpreting the phenomonological history of the world. In this sense, Darwin’s theory was not simply another philosophical conjecture about the origins and nature of life; rather, it was an organizing principle based upon observations and experience of the physical world. Just as the Christians had their Bibles to tell them about origins, so natural history became, to evolutionary theory, a new Bible through which to interpret the world.

So what does Darwin’s “bible” tell us about death? Simply stated, death must be seen as a natural part of the universe.

Cosmology and Biology: Coming to Terms with Death as “Natural”

Let’s start from the beginning. Scientists tell us that our bodies are composed of carbon? But

where did all this carbon—the very building blocks of our physiology—come from? Cosmologists note that it is the creation, destruction and dispersion of stars that has provided the constituent elements that of which our bodies are composed. However, the only way in which this carbon could eventually “reach” the earth to provide the basis for our physiology is through the birth and destruction of these very stars. As stars take millions, if not billions of years to grow, burn out, and disperse, the composition of the human body is a vignette of the history of the universe. What is this history? It is a history of billions of years of death, of the organization, disruption and dispersion of the various elements of the universe. In effect, those who would describe this history as “bad” are, in essence, denigrating their very selves, for it is upon the back of this violent cosmological history that the human body is ultimately composed.

where did all this carbon—the very building blocks of our physiology—come from? Cosmologists note that it is the creation, destruction and dispersion of stars that has provided the constituent elements that of which our bodies are composed. However, the only way in which this carbon could eventually “reach” the earth to provide the basis for our physiology is through the birth and destruction of these very stars. As stars take millions, if not billions of years to grow, burn out, and disperse, the composition of the human body is a vignette of the history of the universe. What is this history? It is a history of billions of years of death, of the organization, disruption and dispersion of the various elements of the universe. In effect, those who would describe this history as “bad” are, in essence, denigrating their very selves, for it is upon the back of this violent cosmological history that the human body is ultimately composed.At this point, some might object, wishing to bifurcate cosmological history and human history. These might affirm the 15-billion year history of the cosmos, yet choose to draw the line of the “natural-ness” of death at the level of humanity. The argument goes something like, “humans, after all, are created in the image of God—therefore, they exist on a different level of relationship to the created order than anything else in the universe.” However appealing such an approach might be, it must ultimately be rejected.

Firstly, it is theologically dangerous to bifurcate humanity from the created order. Such an

approach ultimately cannot be reconciled with the biblical record, for humanity is claimed to have been created from the “dust” of the earth. Therefore, if its “dustness” is to be affirmed in a meaningful and intellectually honest way, humanity must be viewed in such a way that humanity’s experience of the physical universe is not diametrically opposed to being made of the same “stuff” of creation.

approach ultimately cannot be reconciled with the biblical record, for humanity is claimed to have been created from the “dust” of the earth. Therefore, if its “dustness” is to be affirmed in a meaningful and intellectually honest way, humanity must be viewed in such a way that humanity’s experience of the physical universe is not diametrically opposed to being made of the same “stuff” of creation.Secondly, denying the natural nature of human death is counterintuitive from a biological perspective. As grade school children learn in science class, the human experience of being “alive” is predicated upon cellular death. The flow of blood, growth and preservation of tissues, etc. is the result of human cells constantly dividing and dying, dividing and dying. Without the division, death, and replication of cells, human anatomy would be impossible to animate. In fact, biological death is precisely defined by the cessation of the cellular growth/replication/death cycle. In this way, then, being physically alive necessarily involves an element of death. Over the span of our lives, we will lose untold billions of cells to “death”; and yet, it is this very death that makes our experience of life possible. With this is mind, it is difficult to conceive of a form of human existence that does not involve death—at least on a cellular level—and yet is consonant with the history of universe.

Much more could be said on this topic. However, it seems the point is sufficiently made. The very constitution of our universe is rooted in “death.” Not only is it a defining characteristic of what exists, but it is also, in crucial ways, the basis for the existence of the human person and its subsequent experience of “life.” In this way, it is difficult to imagine how it is possible to speak of “death” as something that is “bad” and against “God’s will,” when death is, in fact, the very mechanism through which God has brought about the whole of creation.

“Good and Bad” and the Morality of Death

At this point, one might raise a few objections. One of them, at least, might center around the human experience of death in a total sense (not just on the cellular level). After all, one might argue, humans do not experience death as “good” or “natural.” There is pain and loss involved. Many are devastated by the death of those they love. How in the world could death be part of a “good” creation?

Admittedly, this is a strong objection. Because it directly intersects the crisis of human experience, it cannot be distilled into a purely theoretical conversation. After all, in the final analysis, people still experience the distress of death and cannot be pacified by philosophical arguments.

I think the answer to this dilemma is to examine the problem: the human experience of the negative evaluation of death.

Very simply, humans assign a “moral” value to death because it dramatically and unavoidably intersects the very experience of “being” human. However, as has already been noted, there is very good reason to believe that death—rather than alien—is actually centrally rooted in what it means to be human and “alive.” From where, then, does the discrepancy in the actual nature and the human evaluation of death arise? I would assert that the answer lies in the ultimate consequences of death, not in the nature of death itself.

As the book of Genesis beautifully illustrates, humanity was created with capacity for relationship with God. Although Adam shares a similar genesis and biology with the rest of creation (“from the dust”), humanity is unique in the sense that within it resides the imago dei, the image of God. While some locate the imago dei in human reason, personality, etc., it can be limited to any one feature of the human person. Rather, the imago dei is expressed in the ability of the human as a totality to exist in a qualitatively different kind of relationship with God than the rest of creation. This relationship is expressed in that it is with humanity whom God converses and it is to humanity that God grants responsibility for the care of creation. Even the recounting of the special circumstances surrounding the creation of Eve represents the relational nature of God and humanity in the garden (“it is not good for Adam to be alone”), for God reveals that humans are more than “just” biological—they are also created for relationship with others and with God.

So…what does this have to do with death? In the Genesis accounts, we are given a picture of humanity’s state of living in the presence of God. Without fear, Adam and Eve live and work in the garden. They exist in harmony with the creation surrounding them, providing care and love for God’s good creation.

But then everything goes wrong. Deceived by the serpent, Adam and Eve disobey God’s

command not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Because of their disobedience, something about them is altered—they take on an entirely new perspective of themselves, God and their relationship to the created order. What was once a natural part of creation now becomes a source of shame (their nakedness). The God who had once dwelled with them and walked with them is now a source of fear. Suddenly, the entire creation is transformed—in their eyes—from something “good,” created with the care and providence of God, to something hostile and violent to them. Unable to properly exist in this environment any longer, Adam and Eve are excluded from the garden, cut off from the Tree of Life that had sustained them.

command not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Because of their disobedience, something about them is altered—they take on an entirely new perspective of themselves, God and their relationship to the created order. What was once a natural part of creation now becomes a source of shame (their nakedness). The God who had once dwelled with them and walked with them is now a source of fear. Suddenly, the entire creation is transformed—in their eyes—from something “good,” created with the care and providence of God, to something hostile and violent to them. Unable to properly exist in this environment any longer, Adam and Eve are excluded from the garden, cut off from the Tree of Life that had sustained them.The curse of breaking the command was that “on the day you eat of the fruit, you shall surely die.” Nonetheless, Adam and Eve ate of the fruit—and didn’t die, at least no “on the day.” So what are we to make of this? Is biological death the proximate result of what the stories of Genesis recount? Or is there something else that is being communicated by these stories?

I would suggest that the death spoken in the Genesis accounts cannot be reduced to biological death. The point of the Genesis stories is not to provide a theological explanation for biological death; rather, the crux of the story is getting at the fundamental problem of humanity. The problem with humanity, according to the Genesis account, is not simply that humans die. Rather, the crisis of sinful humanity’s existence is that humanity is separated from the presence of God. The Garden is where God dwells. It is by the presence and power of God’s spirit that human life is understood to exist (“the breath of life”). Corrupted by pride and disobedience, humanity cannot dwell in the presence of God. It is not so much that God excludes, but the humanity excludes itself. In its sinfulness, humanity reevaluates its nature as created by God. For example, in viewing themselves with “opened eyes,” they called their nakedness “shame” when God had called it “good.” Because of this dichotomy in judgement, humanity cannot dwell with God for it will persist in denying that which God has called “good,” replacing it with its own sinful assessments.

I think this conception of “separation from God” gives us a helpful insight into the problem of death. Death is not “bad” because it is negative in and of itself. In proper relationship to God’s will, death is part of the creative structure of the universe. However, when analyzed by the experience of sinful humanity, death is called “bad.” This occurs for at least two reasons.

First, death is diametrically opposed to human autonomy. Sinful humanity’s sole driving force is to assert itself against the will of God. Death, however, mitigates against this because it is something that sinful humanity cannot overcome; it remains a part of the power of God in creation and cannot be subverted by human designs.

Second, death exacerbates humanity’s separation from God. In proper relationship to God, humanity need not fear death, for it can trust in the goodness of God to accomplish God’s good and pleasing will in human life and death. However, to sinful humanity, separation from God is the terrifying self-annihilating confrontation with non-existence. As humanity’s existence is based upon the power of God’s life-giving Spirit, separation from God is a hopeless existence that can hope for nothing but disillusion.

Because of these reasons (and many others that will not be mentioned here), it is not difficult to see why death is assessed so negatively in human experience. Death becomes a negative reality for humanity precisely because sinfulness transmutes death into a reality-negating force. In human relationships, we are pained by death precisely because our separation from God as sinful humans precludes us from any hope for loved ones who have died. Separated from the presence of God, those who have no existence to us, and merely proclaim the fate that we seek to escape, but inevitably cannot.

So what does this have to do with PSA theory? Let me try to bring this around full circle. As noted earlier, the baseline assumption of PSA theory is that “The penalty of sin is death.” If Christ, in his death, “pays” the penalty for humanity, it would follow that no penalty remains. This should mean that those for whom the “penalty” is paid should not die, for to die would be a consequence of the “penalty.” Yet all humans—Christian and not—die. This is a problem.

However, a bigger problem is that “death” within the confines of PSA theory is seen as something from which humanity needs saving. As I showed above, it is very difficult to scientifically speak of death as something that is “alien” to the created order. Rather, it is an intrinsic part of creation, and is even utilized as a mechanism in creating life. Therefore, to assert that death is something from which we need “saving” is to undermine our very createdness. It is, in effect, to call the good creation of God “bad,” and requires that God recant in the purpose and design of creation just so that God can rescue humanity.

Moreover, it distracts from the real problem that plagues humanity, a problem from which

“rescue” from death will not save—separation from God. After all, if death is a natural part of existence for human creatures, it does not follow why it would be something from which humanity needs saving. To locate humanity’s problem in the natural event of biological death is to completely miss sight of why death is perceived as a negative reality. We do not fear death because we fear biological death. Our entire lives are caught up in biological change—it is something in which we are caught up from the first moment of consciousness. Rather, we fear change and death because it reminds of our dilemma, of the myriad ways in which we are separated from the life-giving presence of God. It is ironic, indeed. Life is the one thing that we desire, and yet our very sinful existence wars against this desire by rejecting God. Though God would be reconciled, we desire the road of Adam and Eve, to define and arrange reality according to our own designs (calling “good” “bad”), thus perpetuating the rift, driving ourselves closer and closer to the precipice of non-existence.

“rescue” from death will not save—separation from God. After all, if death is a natural part of existence for human creatures, it does not follow why it would be something from which humanity needs saving. To locate humanity’s problem in the natural event of biological death is to completely miss sight of why death is perceived as a negative reality. We do not fear death because we fear biological death. Our entire lives are caught up in biological change—it is something in which we are caught up from the first moment of consciousness. Rather, we fear change and death because it reminds of our dilemma, of the myriad ways in which we are separated from the life-giving presence of God. It is ironic, indeed. Life is the one thing that we desire, and yet our very sinful existence wars against this desire by rejecting God. Though God would be reconciled, we desire the road of Adam and Eve, to define and arrange reality according to our own designs (calling “good” “bad”), thus perpetuating the rift, driving ourselves closer and closer to the precipice of non-existence.As seen, the problem of separation is not just a matter of “life and death”—rather, it concerns the very crisis of being and non-existence. There is more to stake here than simply making it to heaven or hell.

(To be continued)

3/14/2006

Oedipus Complex

By Grace Green

MARSEILLES, France -- Skirt-chasing playboy Daniel Anceneaux spent weeks

talking with a sensual woman on the Internet before arranging a romantic rendezvous at a remote beach -- and discovering that his on-line sweetie of six months was his own mother!

talking with a sensual woman on the Internet before arranging a romantic rendezvous at a remote beach -- and discovering that his on-line sweetie of six months was his own mother!"I walked out on that dark beach thinking I was going to hook up with the girl of my dreams," the rattled bachelor later admitted. "And there she was, wearing white shorts and a pink tank top, just like she'd said she would.

"But when I got close, she turned around -- and we both got the shock of our lives. I mean, I didn't know what to say. All I could think was, 'Oh my God! it's Mama!' "

But the worst was yet to come. Just as the mortified mother and son realized the error of their ways, a patrolman passed by and cited them for visiting a restricted beach after dark.

"Danny and I were so flustered, we blurted out the whole story to the cop," recalled matronly mom Nicole, 52. "The policeman wrote a report, a local TV station got hold of it -- and the next thing we knew, our picture and our story was all over the 6 o'clock news. "People started pointing and laughing at us on the street -- and they haven't stopped laughing since."

The girl-crazy X-ray technician said he began flirting with normally straitlaced Nicole -- who lives six miles away in a Marseilles suburb -- while scouring the Internet for young ladies to put a little pizzazz in his life.

"Mom called herself Sweet Juliette and I called myself The Prince of Pleasure, and unfortunately, neither one of us had any idea who the other was," said flabbergasted Daniel.

"The conversations even got a little racy a couple of times.

"But I really started to fall for her, because there seemed to be a sensitive side that you don't see in many girls.

"She sent me poems she had written and told me about her dreams and desires, and it was really very romantic.

"The truth is, I got to see a side of my mom I'd never seen before. I'm grateful for that."

When starry-eyed Daniel asked Sweet Juliette to send him a picture, Nicole e-mailed him a photo of a curvy, half-clad cutie she'd scanned from a men's magazine.

"The girl in the picture was so beautiful, I begged Juliette to meet me on the beach -- and Mom said yes," he recalled. "Mom says she was falling for me, too, and she just wanted to meet me, even though she knew I'd be disappointed when I saw her.

"As for me, I figured I was going to find the girl of my dreams.

"I guess that's about as wrong as I've ever been."

Daniel admits he and his mother could do little but stammer and stutter around each other for days after their cyberspace exploits came to light. And his father Paul -- Nicole's husband of 27 years -- wasn't too happy when the story hit the news and his beer-drinking buddies made him the butt of their jokes.

"Dad was ticked for a while and he forbid Mom to talk to anybody on the Internet ever again," said embarrassed Daniel.

3/09/2006

Omnipotence...Part Deux

A few weeks ago, I noted some preliminary issues relating to the subject of God's "omnipotence." In this, I discussed whether or not the concept of "omnipotence" is a helpful concept for understanding the parameters and possibilities of divine action. After a bried examination of some of the seminal philosophical issues involved, I concluded that the concept of "omnipotence" is ultimately unhelpful in critically describing the nature and possibility of divine action, as the definition of "omnipotence" must eventually be reduced to a tautology--i.e., "God can do that which God can do."

A few weeks ago, I noted some preliminary issues relating to the subject of God's "omnipotence." In this, I discussed whether or not the concept of "omnipotence" is a helpful concept for understanding the parameters and possibilities of divine action. After a bried examination of some of the seminal philosophical issues involved, I concluded that the concept of "omnipotence" is ultimately unhelpful in critically describing the nature and possibility of divine action, as the definition of "omnipotence" must eventually be reduced to a tautology--i.e., "God can do that which God can do."Continuing on, I would like to briefly note some issues relating to the relationship of human logic and divine ability. This discussion is actually bourne out of conversation in which I have been engaged in a discussion forum at christianforums.com. The questions posed were, "Can God do that which is logically impossible, such as make a square circle?" and "What is the relationship between logical and God's action?" The following is my response to the questions:

Logic is defined by God's actions and nature, not the other way around. God is not unable to do the impossible. After all, as the action of God determines that which is within the realm of possibility, any "impossibility" does not have actual existence. In this sense, God is not incapable of doing anything, for one cannot be incapable of doing that which does not exist as a possibility.

In an irrelevant sense, God is theoretically incapable of doing a lot of things. However, as God is the very ground of that which exists as possibility, the "impossibilities" do not have existence and, therefore, should not even be brought into question.

It would be like asking, "Is it possible for God to not exist?" While it is theoretically possible to conceive of non-existence, non-existence for God is impossible. After all, one has to "exist" in order to non-exist, for the non-existence of something cannot be established without it's previous (or concomitant) existence. Therefore, even though it is impossible for God to not exist, the "impossibility" is not an "actual" and is therefore a non-entity when applied to God.

The same rule applies to the "rock" question. One could say it is impossible for God to create a rock so big that God can't lift it. However, the potential for something to exist which is greater than God is a non-entity, and the actual existence of such would violate the preceding argument about God's non-existence. So then, as with the example of non-existence, the impossibility of God creating a rock so big God can't lift it is an absurdity, and not an actual inability.

Although I think this argument is sound in relation to describing the parameters of God's action, it simply serves to support my original thesis that the concept of "omnipotence" is ultimately unhelpful for actually describing the nature of the action of God. As shown above, the "possibility" of God's actions is precisely defined by that which God does. It is not "possible" to conceive of impossibility for God, as the possibility of any "actual" is based explicitly in the action of God. Therefore, once more, the definition of "omnipotence" is reduced to, "God is able to do that which God is able to do." Moreover, as the very definition of "possibility" of action is defined by the very acts of God, the definition of omnipotence could actually be further reduced to, "God does that which God does."

3/07/2006

Does God Suffer?

Aristotle argues that God cannot suffer, for a suffering God would be a God subject to change. To Aristotle, the perfection of God is located in God's changelessness. The logic proceeds that if God were to decrease in perfection, obviously God would cease to be perfect, and therefore, cease to be God. Moreover, if God were to increase in perfection, such increase would indicate that God had not previously been complete in perfection, thus negating God's supposed divinity. So then, to Aristotle, any "passion" (change) on God's behalf is effectively self-negating. Although I appreciate the power of Aristotle’s argument concerning the necessary immutability of God, at the end of the day I am unconvinced. It seems fairly arbitrary to define perfection as ‘changelessness.’ While I do understand Aristotle’s rationale, his argument seems blind to the counter that in preserving God’s unqualified “changelessness,” one has also effectively stripped God of any ability to act, thus reducing God to a benign deity lost in perpetual and eternal self-contemplation.

Aristotle argues that God cannot suffer, for a suffering God would be a God subject to change. To Aristotle, the perfection of God is located in God's changelessness. The logic proceeds that if God were to decrease in perfection, obviously God would cease to be perfect, and therefore, cease to be God. Moreover, if God were to increase in perfection, such increase would indicate that God had not previously been complete in perfection, thus negating God's supposed divinity. So then, to Aristotle, any "passion" (change) on God's behalf is effectively self-negating. Although I appreciate the power of Aristotle’s argument concerning the necessary immutability of God, at the end of the day I am unconvinced. It seems fairly arbitrary to define perfection as ‘changelessness.’ While I do understand Aristotle’s rationale, his argument seems blind to the counter that in preserving God’s unqualified “changelessness,” one has also effectively stripped God of any ability to act, thus reducing God to a benign deity lost in perpetual and eternal self-contemplation.Historically, the Church has adopted the categories provided by Aristotle, affirming that God is "impassable." For centuries, Christian theology has located the suffering of Christ within the human nature of Christ while concomitantly affirming the impassability of Christ's divine nature. An obvious result of this has been a bifurcation between the divine and human natures of Christ, leading to a potentially restricted and somewhat disconnected conception of the relationship of the divine to human nature and experience. Despite the central place which the doctrine of the impassability of God has enjoyed in historical Christian thought, recent theological exploration has reconsidered the categories provided by Aristotle, rejecting them in favor of the biblical witness and theological necessity of engaging the whole person--not singular human nature--of Christ in the suffering endured on the cross. Seminal in recent scholarship has been The Crucified God in which Moltmann describes not only the suffering endured by the Son on the cross, but also the suffering which the Father experienced in relation to the death and rejection of the Son at the hands of sinful humanity.

Now, to get right down to the question, I believe the answer is “Yes,” God does suffer. I think this is necessitated by the Christian proclamation that “God is love.” For example, a great definition of love (at least in my mind) is that of complete self-giving, a definition which is poignantly displayed in Christ’s ultimate self-giving of himself to humanity and to the Father’s will in the cross. However, this “self-giving” is total, in that one gives oneself to others while concomitantly taking into one’s own person the totality of the other.

Therefore, if Christ truly represents the total self-giving (love) of God in being made “sin” for us, this means that in giving himself to us, Christ has concurrently encountered, in his very person, the full depths of human sinfulness. As Paul Jensen wonderfully point out, in this self-giving, Christ “…[absorbs] into his own being the consequences of human sin.”* This encounter with human sinfulness cannot simply be located in the “human” side of Christ. Rather, as the consequence of sin is death (separation from God), it is clear that Christ, in the fullness of his person, is subject to the full judgment of sin and dies, feeling the unbearable weight of separation from the Father.

However, despite Aristotle’s fear that a “passioned” deity would be self-contradictory and negating, the suffering of Christ is actually the means by which the fullness of God’s love is revealed to humanity. Although Christ is indeed subject to the full wrath and power of the consequences of sinfulness, he is not defeated. Moreover, even though Christ has “absorbed into his own being the consequence of human sin,” this very act of self-giving love is the means by which sin and death are overcome, their powers exhausted in his very person.

In this answer, I have perhaps strayed a bit too far into Atonement theology. However, I believe this is necessary for, as Luther powerfully pointed out, God is not to be known in abstraction. Rather, the cross is the paradigm through which we are to approach the knowledge of God, for it is through the suffering and death of Christ that the true “face” of God is revealed. Therefore, this “theology of the cross” compels us to rethink the question not on the basis of whether a “suffering God” is possible, but rather because this is precisely the way in which God has revealed the divine nature, purpose and love. For a world of people separated from the only source of life and suffering at the hands of evil people, systems of oppression and the capriciousness of the physical world, the question of whether or not God can suffer is most prescient. After all, within this question lies the only hope of human salvation.

*Paul Jensen, “Forgiveness and Atonement,” Scottish Journal of Theology 46 (1993): 141-159 at 154.